Week 3: The Charles River

Riparian poetry, "beast entralls and garbidg," water birds, and Cambridge's most famous literary suicide.

“Oh, the river! … I know it's like me … I know that I belong to it. I know that it's the natural company of such as I am! It comes from country places, where there once was no harm in it—and it creeps through the dismal streets, defiled and miserable—and it goes away, like my life, to a great sea, that is always troubled—and I feel that I must go with it!” - Charles Dickens, David Copperfield

Early on a frigid Sunday I leave my house, running north through Brookline in the direction of the Boston University Bridge and the Charles River. To reach the river, I must cross two sets of trolley tracks (the B and C), one highway interstate (I-90), one commuter rail line (Framingham-Worcester), a riverside park (the Esplanade) and several protected bike lanes (which I ignore).

Approaching the Charles from this direction is always a shock, for in Brookline you hardly notice the river at all until you’re on top of it. To the west, it slumbers through Cambridge and Alston, Harvard’s trim and tidy bridges crisscrossing it like cutlery laid out for a club dinner. To the east, the river is all ocean—a canvas of shimmering wavelets and seagulls with the city rising Atlantis-like in the background.

I Have Known Rivers

I cross the river and follow its tightening bends along Memorial Drive, thinking about the many times I’ve crossed and re-crossed this same length of water. Visiting Boston in high school, I used to ride the Red Line over the Longfellow Bridge (affectionally called the “Salt and Pepper” bridge after its shaker-like pedestals) and would always get close to the train’s window as it rose from the tunnel, delivered a stunning view before plunging back into darkness and the long climb to Davis Square.

When I first moved to Cambridge in 2019, I was still teaching outside the city, and my daily commute would begin and end by crossing the Charles in my old Volvo. One pitch-black winter morning I took a right turn onto the Cambridge Street bridge and found to my terror that I was heading the wrong way into oncoming traffic. Fortunately, there were only a few cars on the road at that hour and I was able to make a sharp U-turn on the bridge to avert a collision. To this day, my heart leaps in my chest whenever I turn onto the Western Avenue bridge, the memory still fresh.

During the pandemic, I relieved my cabin fever by walking before sunrise along the river by the Longfellow House—the site of George Washington’s war headquarters in 1775-76—and down to the Anderson Bridge and the Harvard boathouses. In the winter, migrating birds make the river’s frozen surface their temporary home. These birds include Buffleheads, Goldeneyes, and Mergansers.

The genus name for the Common Goldeneye is derived from the Ancient Greek word “bullheaded,” and indeed these birds are aggressive and territorial. You need to be, I suppose, if you spend your winters on a frozen river and the other half of the year in the deep woods of Canada. Mergansers, meanwhile, are a water bird whose name translates to ‘diving duck’ in Latin (mergus = diver, anser = goose). Dr. Samuel Johnson, who gave the English language its first dictionary, defined a merganser as “a large waterfowl proverbially noted, I know not why, for foolishness.” Foolish and bullheaded are the birds who winter on the Charles, and perhaps the humans who do too, for what else but poor judgment and obstinacy could explain such behavior?

Drowned in the Fading of Honeysuckle

The Charles is not one of the world’s great rivers. It has welcomed no Brooklyn Bridges, birthed no pyramids, inspired no Whitmans or Twains. It is short, slow-moving, and not particularly deep (only around 15 feet at its head and 2-3 feet in its tail). While Boston’s harbor is a commercial powerhouse, the city’s river has always been of limited industrial use. It is a recreational river, good primarily for rowing, kayaking, and running alongside.

It is also, and has been for four centuries, an unclean river. But as the Standells song confirms, Bostonians have learned to “love that dirty water.” Where other cities swell with pride at the majesty of a Hudson, the mystery of a Monongahela, the history of Delaware or the placidity of a Potomac, Boston revels in the tooth-bitten grubbiness, the shabby gentility, of this most intellectual of rivers.

The water is not fine, but let us nonetheless dive in.

In William Faulkner’s novel The Sound and the Fury, the Southerner Quentin Compson wakes up one morning in his Harvard dormitory, and after spending a day traversing Cambridge and Boston, realizes that he is in love with his sister Caddy and cannot cope with the fact that she has had intercourse while he (Quentin) is still a virgin, and decides to kill himself by jumping into the Charles. As in a Greek play, the violent act happens off-page, but it remains one of the most famous suicides in literature and is in the running with Henry James as the best-written book set in the Boston environs.

I think a lot about Quentin and his fatal jump, particularly as I pass the many Harvard bridges on my long run. Scholars have spilled far too much ink trying to figure out the precise location where Quentin jumped to his death. A few years ago, some devoted Faulknerians erected an unofficial plaque commemorating their doomed literary hero. (Sadly, the plaque has since been removed by some illiterate Cambridge city hall employee with no appreciation for what makes life worth living.)

The fact that academics have tried to deduce where a fictional character is supposed to have committed suicide on an actual river tells us two important things: 1) don’t get a PhD in English literature, and 2) Faulkner is a great master.

Here is Quentin as he sits looking out at the Charles, at the rowers as they go by, his thoughts leading inevitably to Caddy and her loss of innocence:

Now and then the river glinted beyond things in sort of swooping glints, across noon and after. Good after now, though we had passed where he was still pulling upstream majestical in the face of god gods. Better. Gods. God would be canaille too in Boston in Massachusetts. Or maybe just not a husband. The wet oars winking him along in bright winks and female palms. Adulant. Adulant if not a husband he'd ignore God. That blackguard, Caddy. The river glinted away beyond a swooping curve.

And here he is later in the novel, crossing the river again in a car with a Harvard classmate as they drive into Boston:

We crossed the river. The bridge, that is, arching slow and high into space, between silence and nothingness where lights—yellow and red and green—trembled in the clear air, repeating themselves.

Rest in peace, Quentin. May we all drown in our own fading honeysuckle.

Learning to Love That Dirty Water

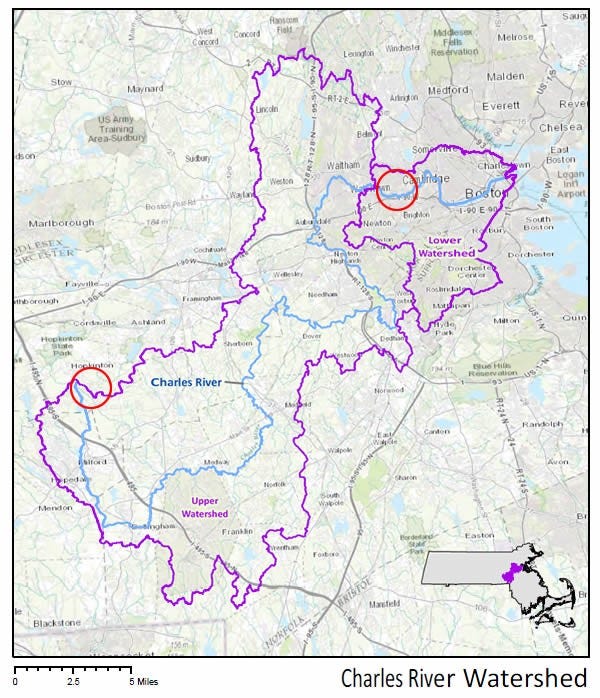

The Charles River flows 80 miles from Hopkinton to Boston. It is the most prominent urban river in New England, a major source of recreation and a readily available connection to the natural world for residents of that elusive region called “Greater Boston.” The entire river is an enormous drain for any and all rain and melted snow that falls in a watershed area of 310 square miles.

The headwaters of the Charles are at Echo Lake in Hopkinton, coincidentally the town where the Boston Marathon begins. Sadly, the marathon route never actually borders the river at any point, though the route itself has a riparian quality, and the eastward flow of runners mimics the water’s progress. From Hopkinton, the river flows through the municipalities of Milford, Bellingham, Franklin, Medway, Millis, Medfield, Sherborn, Dover, Natick, Wellesley, Needham, Dedham, Newton, Waltham, Watertown, Cambridge and Boston, and from there into Boston Harbor, Massachusetts Bay, and the Atlantic Ocean.

Despite its appearance of restful slumber, the "Lower Charles"—the area from the Watertown Dam to Boston Harbor—is actually one of the busiest recreational river segments in the world, stuffed up with boat houses, jogging paths, sports fields and ampitheaters.

While its current today may seem steady and strong, the Charles is actually a reanimated zombie of a river, the product of centuries of reclamation, redirection, draining and salvaging. It is not quite a man-made river, but nor is it some rustic stream of romantic naturalism either. Like most great things, it had a difficult birth.

The pollution started early. In 1632 the Massachusetts General Court approved the construction of a weir on the river at the fall line in Watertown. Two years later the first mill was built at the same site: there would be 43 industrial mills built on the lower Charles through the years. By 1656, the Charles was already beginning to get a reputation for filthiness: an ordinance of that year permitted the dumping of “beast entralls and garbidg” without a fine.

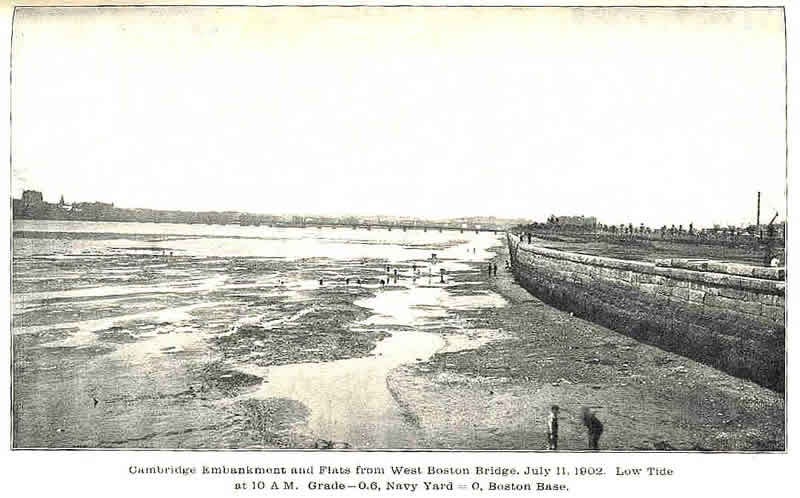

As Boston urbanized and began paving its streets, rainwater runoff polluted the river with lead and other toxic chemicals, killing fish and leading to algae growth. A granite seawall was built on the Cambridge shore, along what is now Memorial Drive.

Through the early nineteenth century, the tidal marshes of the Charles were filled up with the land removed from the three hills of Boston. The most prominent of these, “trimountain” (now Tremont) was flattened in order to fill in the area around Charles Street. Boston was, to the early settlers, an island of many hills. One can see this in early paintings of the city. Sadly, all but one of these hills was pushed into the water to make way for more urban land. The last vestige of Boston’s former mountainous glory is Beacon Hill. Here’s the view of the seawall at low tide in 1902:

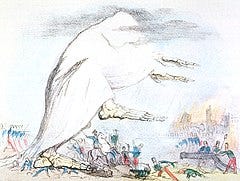

Bacteria in the river exploded in the mid-1800s, leading many to believe that the foul-smelling odors of the river’s exposed mudflats were the cause of disease. In the dark days before Dr. Fauci, the medical profession believed in something called “miasma theory,” which held that diseases from cholera to chlamydia were caused by “bad air” which emanated from rotting organic matter. Please enjoy this wonderful 1831 lithograph of a big sleepwalking skeleton in his nightie:

Hygiene did not improve with the construction in 1878 of the city’s first sewer, which only lowered the river table further and created more tidal flats. The solution to this came with the creation of the Back Bay “Fens,” an artificial marsh with a tide gate to keep the water level of the river permanently elevated. The Muddy River was diverted into a culvert under Brookline Avenue into the Charles which, sadly, killed the Muddy’s natural habitat in the process. This is still an issue today — the Muddy regularly overflows as a result of this 1878 culvert, and a $100 million Muddy River Flood Risk Management Project is, in typical Big Dig style, still in the works. (But worry not! We’re only 20 years into “Phase 2”!)

Over the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Charles was basically put on river testosterone at the expense of all the surrounding tributaries, which were “culverted” to raise the Charles’s water-level. (Culverting involves getting a current to flow in an underground pipe into another river.)

A land many rivers became a city with one. Requiescat in pace Stoney Brook, Faneuil Brook, Village Brook, Tannery Brook, and Laundry Brook! Beautiful brooks, with names like copper coins. The domestic familiarity of colonial Boston’s soft streams—estuaries where Puritans washed their clothes, boys went fishing, and artisans plied their trades—were channeled away, ferreted underground to bring forth the surging currents of a grander, though perhaps less gentle, municipal Boston.

As you walk over the paving stones, pause and listen. Beneath the clamor of the modern world, can you hear the babbling brooks of the eighteenth century deep moving below your feet? Can you hear the water flowing underground? Probably not: it is most likely the sound of someone sipping bubble tea on Boylston, and you’d better keep walking, or someone is going to bump into you.

The River at Night

Preparing for an April marathon means starting your training in the dead of winter. With the shortest day of the year approaching, I try to take advantage of the little daylight by running midday. Still, the Charles is at its best as the sun goes down.

At night, especially in winter, the Charles becomes an alien world of moonbeams and arctic wind. A poem, “Charles River Nocturne,” by the classicist and poet Robert Fitzgerald (born in 1910, the year of Quentin’s death) captures the mood beautifully:

Reflecting remote swords, chilled in the calm / And liquid darkness, lights on the esplanade / Prolong the night’s edge downward all night long / To those whose nostrils ache with the strong darkness, / Those who in hunger press against the waters / Those without birth or death, to whom the cold / Ocean long laboring in her regal womb / Whispers a word of foam. / The lavish cars / Move westward in an eddy and dance of shadow / Under the dazed lamps on the lifeless shore.